Jory family part of Salem since 1848

Statesman Journal

March 18th. 2001

Story has been reprinted with the permission of the

The Salem Statesman Journal.

Florence Baer will be there in spirit as the Statesman Journal celebrates its 150th anniversary this year. So will Beverlee Koutny of Hubbard, Richard Page of Portland, Michelle Jory and Marilee Bell of Salem. For these Jory family members, whose ancestors settled in Salem in 1848, the newspaper's birthday is like one of their own. For 150 years, the newspaper has been like a member of the family, always there for major milestones and setbacks, always recording the events of their lives.

A joyous addition to the family? See birth announcements, a death in the family? See obituaries.

Personal triumphs, personal tragedies; they were documented in the pages of the Capital Journal and the Oregon Statesman, which later merged and emerged as the Statesman Journal.

Even before Florence Baer's father told her to put together a family record, her cousins Elmo and Gladys Jory were snipping clips.

Their scrapbooks of newspaper stories and records held the information she needed to check facts and fill gaps.

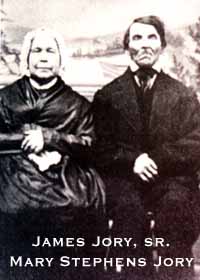

"This has reminded me how important it is for the printed record to be reliable," said Baer, the 85-year-old great granddaughter of English immigrant James Jory.

Their lost oxen and cattle auctions were advertised on its pages. Milestones such as attaining U.S. citizenship and obtaining land grants were announced in public notices.

Generations of Jorys didn't just show up in newsprint, but on the newspaper's delivery routes, production floors and customer lists.

Beverlee Koutny remembered how her father, who despised farming, delivered the paper on one of the rural routes. He and her mother had married young and the job helped with finances.

Page remembered fashioning toy soldiers from the lead scraps on the floor of the production room where newspaper employees operated the Linotype machines.

Baer's brother, 87-year-old Salem native Wilbur Jory, remembered when genealogy was nothing more than what happened yesterday. Although he has absolutely no interest in family history, he is a lifelong subscriber to the paper.

Pioneer Jorys

Had it not been for a law where 9-year-old children could be taken from their families for apprenticeships, the Jorys might never have ended up in Salem.

With a brood to protect, James and Mary Jory left England in 1930 in

search of opportunity. Their eighth child was born in Canada.

Tired of the poor soil there, the family left for central Canada but was detoured by a Missourian who told them about the rich land back home. He was right, but the Jorys believed slavery was wrong. So the family moved to Illinois, a free state.

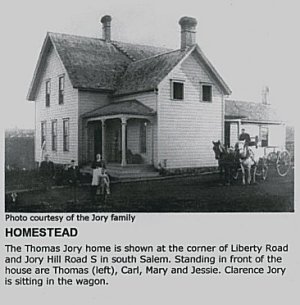

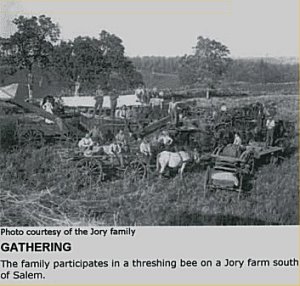

One of their sons, fearing for his wife's health because of the malaria outbreak, suggested moving to Oregon. The family arrived in Oregon City on Christmas Day 1847, and settled in the hills of Rosedale six miles south of Salem in 1848. At one time, the Jorys owned more than 2,000 acres. Today, a cemetery, park and a road bear the family's name.

Yet there was a time when Baer had to prove that she was a Jory.

She had to show her birth certificate for a job at an airplane factory job, but since she was delivered by an uncle, the family wasn't sure there was a birth certificate.

Fortunately, the newspaper had run her birth notice in 1915.

"This was part of the proof they wanted," Baer recalled.

Industrious standards

Other Jorys also have found the paper useful.

Koutny remembered her great-grandfather looking up the price of eggs and butter to see what his could sell for.

She gleaned a lot of family genealogy from the paper, as well.

"Those were wonderful obits they used to write," said Koutny, 69. "What they accomplished during their lifetime, who they were related to. We had some wonderful inventors which were noted."

There was Oliver Jory, inventor of a fruit dryer, and other Jorys who came up with a swivel plow, grain separator and other inventions.

There were Jorys considered industrious, even by family standards.

While in college, Elmo Jory lived in a tent during the dead of winter to cut expenses to $7.50 a month or less, not even half the budget for the average student. He spent $1 to rent the ground for his tent, and cooked his own meals and studied in the library. He graduated from the Oregon Agricultural College (now Oregon State University) in Corvallis in 1918 with a degree in pharmacy.

Famous Jorys

Every family has its skeletons and its stars.

Victor Jory, the movie, stage and television actor, made headlines when he led a group of actors and screenwriters to Salem in 1951 for Movietime, USA, 50th anniversary of motion pictures. He played Injun Joe in "adventures of Tom Sawyer," Tara's overseer in "Gone With the Wind," and Helen Keller's father in "The Miracle Worker." He made the news again during his Salem visit to keep a vigil at his father's deathbed.

"He was an exciting person," Baer recalled.

Edwin Jory, his dad, also had his share of the limelight. He was in an 1890 photo of the Red Hills baseball team, named after Rosedale's distinctive soil."

The prune farmer again made headlines when he donated 27 acres of the original 640-acre land grant for a public park that opened in 1965. Marion County now owns and maintains Joryville Park, the resting place of little Ella Jory.

The child who died of a "putrid sore throat" at age 4 was buried under a maple tree in 1862. The paper carried her obituary and a poem by her father William, one of James' sons. A stanza from the poem reads:

Yes, darling of our social joys,

'Tis hard to part with one so dear;

To miss thee in thy childish plays,

To miss the object of our care.

Page's father, Everil Maxwell Page, was appointed by Gov. Charles

Sprague to the Circuit Court. The Salem lawyer who taught law at Willamette University later sat on the state Supreme Court. He died in 1959.

Page's father, Everil Maxwell Page, was appointed by Gov. Charles

Sprague to the Circuit Court. The Salem lawyer who taught law at Willamette University later sat on the state Supreme Court. He died in 1959.

"There was an editorial praising him as a man of great accomplishments,"said Richard Page, whose great-great grandfather was James Jory.

Making the paper

Page remembered how his mom would read the society page in the late 1930s and 1940s to find out about the parties and people.

"She knew everything about everybody," Page, 74, said about Jeryme English, the Oregon Statesman's society writer.

Although the family took three papers - the Oregonian, the Capital Journal and the Oregon Statesman - the Statesman was the favorite because it was a morning paper.

Many readers would go straight to Charles Sprague's editorials. The Statesman publisher was a popular and influential writer before he became governor.

Koutny, whose great-grandfather and Baer's dad were brothers, remembered Harold Jory, registrar at Willamette University, when she was a student there from 1949 to 1951.

"He managed to help me get a job on campus so I could pay my tuition," she said.

The newspaper reported his paralyzing stroke and death in 1958, and the addition of his name to the Willamette scholarship honoring Thomas Jory, his father and a math professor and department head.

Young Jorys

Unlike Richard Page, who was born and raised in Salem, Marilee Bell hardly knew her roots until she moved to Salem in 1975. Bell's grandfather, a Jory descendent, mentioned the family, but it was the Washington state relatives who got the attention.

But when Bell found out in 1992 that the county was about to sell the Jory Cemetery to a developer, she and other Jory descendants quickly organized to block the sale. The county was carrying the 1.5-acre property on its tax rolls for non-payment of taxes.

The newspaper's coverage from 1992 to 1993 not only stopped the county from selling the cemetery, but also led to the formation of the Jory Family Association and several reunions.

It was a life-changing experience," said Bell, 47, a mother of three.

New traditions

Michelle Jory knows that feeling.

At 27, she's just beginning to learn about her roots. It was her grandfather, Lewis Jory of Albany, who told the county some 20 years ago that at 77, he couldn't maintain the cemetery.

As her family knowledge grows, so does the responsibility to preserve it for other generations.

She's getting married soon, but will keep the Jory name for herself and her baby Isabelle.

"It's a sense of pride."

Baer is glad there are younger Jorys to take over the job her dad gave her some 40 years ago.

She remembered how he knew all the stories, but not the dates, because "he was it. He was the history."

Statesman Journal librarian John Marikos provided research for this report.

Susan Tom can be reached at (503) 399-6744 or at stom@StatesmanJournal.com.